Before anyone feels the urge to say, “Then go back to where you came from,” let me save you the trouble.

After you.

Let’s be clear. This country wasn’t discovered, and it certainly wasn’t settled through peace or consent. It was seized through violence and displacement—a history that still shapes how the disease of unease aka paranoia is perpetuated today.

Let me explain.

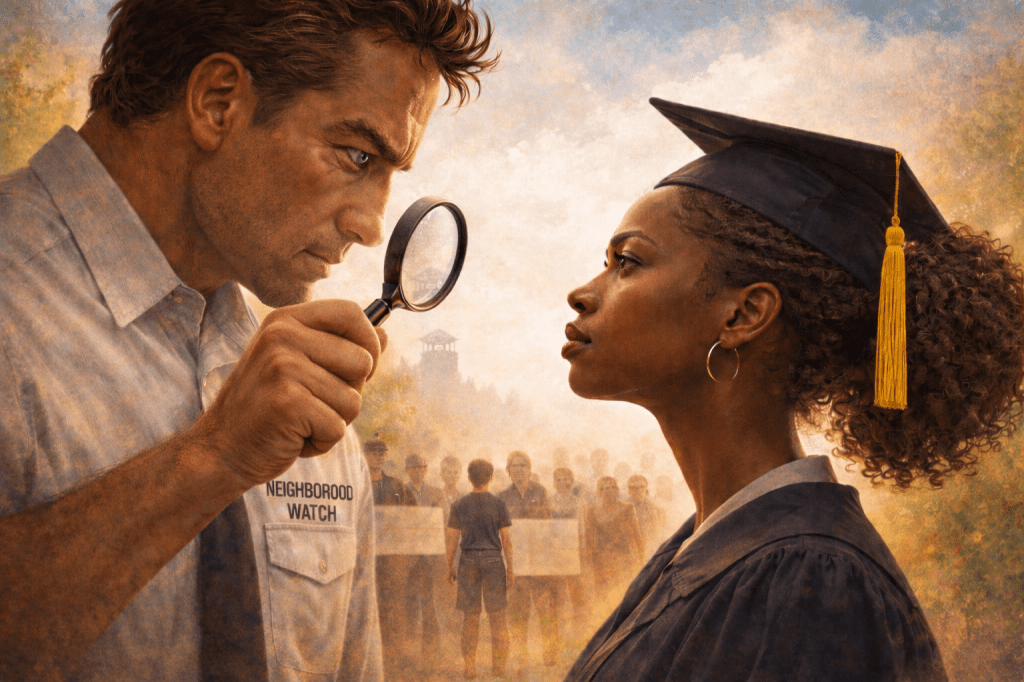

If you’ve ever dealt with a bully at work, at school, online, or in your own neighborhood, you’ve probably noticed something that doesn’t quite add up. For someone who seems so loud, so certain, so invested in asserting dominance, they are oddly preoccupied with what other people are doing.

Watching.

Commenting.

Provoking.

Waiting.

That’s because the bully, at his core, isn’t driven by confidence, but by fear and insecurity.

Insecure people struggle when others move freely, succeed quietly, or refuse to perform within the confines of the role expected of them. Instead of turning inward to examine that discomfort, they turn outward to examine the world. They poke. They test. They assert rules no one asked for. Not because something is wrong with the target, but because something feels unsettled inside themselves.

That ‘something’ is the fact that they can’t seem to understand how after all of the pain, suffering, and utter chaos they’ve inflicted upon others, retaliation still hasn’t arrived at their door.

How Progress Was Policed

American history shows us what happens when minority groups prioritize social progress over all else. Whenever these groups gain education, visibility, or economic footing, the language of fear-mongering suddenly appears in the form of warnings about “law and order,” “protecting our way of life,” “outside agitators,” and the need to “maintain standards” or “keep the peace.” It surfaces not because threat is imminent or has occurred, but because hierarchy has been (or is at risk) of being disturbed.

Post-emancipation, Black Americans didn’t retreat or collapse. They built schools, churches, newspapers, businesses, and political organizations. They bought land. They voted. They participated. The problem wasn’t one of violence. It was one of independence.

In response, states introduced poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses to limit Black political participation—policies that appeared neutral on paper, but were designed to exclude. Segregation laws followed, reinforced by intimidation tactics and violence, all framed as “maintaining standards” or “keeping the peace.”

Did you know?

In 1921, the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, often called “Black Wall Street”, was one of the most prosperous Black communities in the United States. Over the course of two days, white mobs, aided by local authorities, burned it to the ground. As many as 300 Black residents were killed, thousands were left homeless, and more than 35 city blocks were destroyed. The violence was triggered not by crime, but by the visibility of Black economic success.

Why Passiveness Incites More Violence

Passivity doesn’t reassure the fearful and insecure. It unsettles them.

In everyday life, you see this when someone tries to provoke you and you don’t respond—not because you’re afraid, but because your attention is focused elsewhere (e.g., on getting through the day; keeping mouths fed and a roof over your head; survival). And eventually, as is the goal, on thriving.

Minding your own business is especially destabilizing to insecure people. It removes their ability to situate themselves in relation to you. There is no reaction to interpret, no emotion to manage, no proof that they still matter in your internal world. And, oh boy, does that part matter.

When they can’t locate themselves in your response, they begin to fill the silence with suspicion.

History shows the same reaction at scale.

During the Civil Rights Movement, protesters practiced disciplined nonviolence, but they also practiced something quieter and more threatening: they kept on keeping on. They organized. They worked. They built families, institutions, and futures. They pursued dignity not in a performative sense, but as a necessity. Rather than easing tensions, this refusal to center fear intensified backlash. Dogs, fire hoses, and mass arrests were deployed not because protesters were violent, but because they refused to orient their lives around appeasing power.

Fear, Projection, and Control

People who are deeply fearful and insecure tend to assume everyone else thinks the same way they do.

If someone knows they would seek revenge if the roles were reversed, they assume others must be plotting the same. This is projection and it’s one of the most powerful engines of violent bullying, including the dehumanization of those deemed to be ‘other,’ at both the personal and institutional level. It feeds an obsession with getting ahead of an imagined threat—an itch to “get them before they get me.”

Lynchings carried out to enforce racial hierarchy offer a stark example of this paranoia at play: between 1882 and 1968, nearly 4,743 lynchings were documented in the United States, the majority targeting Black Americans. These were not random acts of violence. They were public spectacles meant to send a message: know your place.

The same psychology fueled the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Roughly 120,000 people, most of them U.S. citizens, were removed from their homes and imprisoned without charges or trials. The justification was not evidence, but fear: they’re not one of us and they might do something.

Patterns in the Present

These dynamics haven’t disappeared. They’ve simply been modernized.

Book bans target history that complicates easy narratives and calls for accountability. Voting laws tighten when participation expands. Protest is framed as domestic terrorism and chaos, even when it is overwhelmingly peaceful. Inclusion is recast as risk rather than opportunity for growth.

The same logic shows up in immigration enforcement. Highly publicized ICE raids are justified as matters of “public safety,” even as families, including U.S. citizens, are separated and communities are conditioned to look away. And when violence reaches someone who does not fit the expected script—cases like the recent murder of Rachel Good, a white woman who no longer functioned as the system required (i.e., who did not defend whiteness at all costs and therefore ceased to be protected by it), the response is often quiet, procedural, and quickly normalized.

This is how moral conflict is managed. People are reduced to categories. Harm is reframed as policy. Repetition breeds desensitization, and desensitization makes dehumanization feel routine enough to tolerate. Cognitive dissonance is resolved through dissociation—by convincing oneself that any easily avoidableviolence was “necessary”, “inevitable”, or “someone else’s fault”.

The Irony History Leaves Behind

The final irony is this…the people most often cast as threats tend to understand something very simple: race is a social construct; blood flows through every human body; and everyone deserves a chance at safety and happiness.

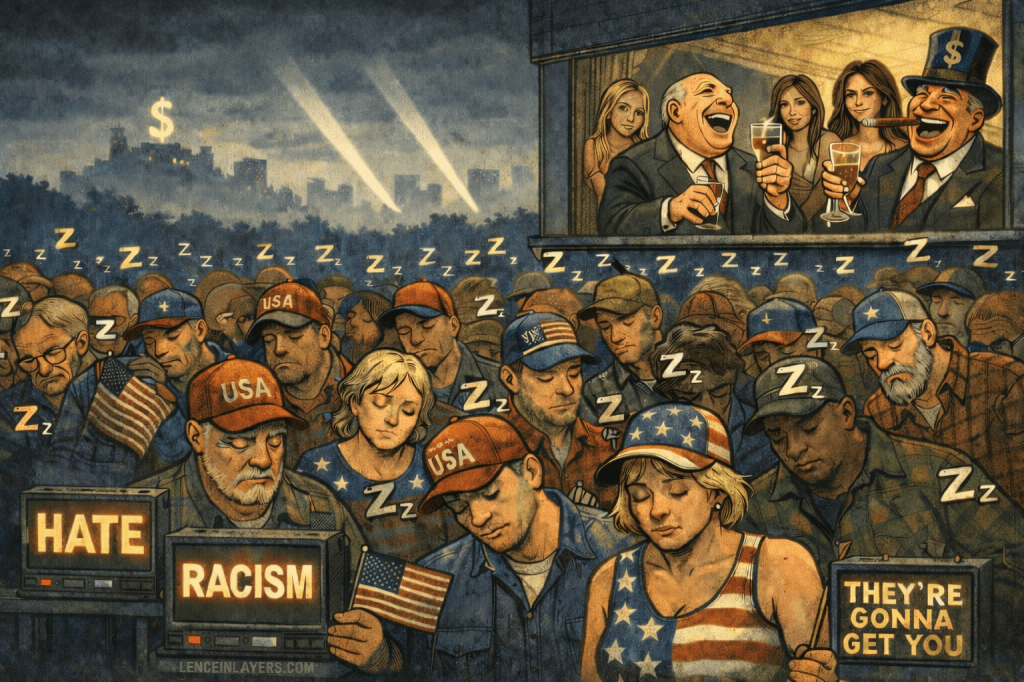

The real tragedy of a bully is that he never recognizes these universal truths. He is recruited to uphold bigotry as both weapon and shield, giving him a sense of purpose while keeping him small, tense, and controlled. As a result, he will spend his entire life policing and demonizing the key to his own liberation.

This is why the word “woke” draws such hostility. It points too clearly at the structure beneath the conflict. It redirects attention upward towards wealth, hoarding, and concentrated power and away from the dangled carrots meant to keep people divided, manageable, and pacified.

History is blunt about this, which is why it’s been the longstanding target of ‘white washing.’

Awareness has never been a threat to ordinary people.

But, it does threaten those who profit from keeping everyone else the opposite of ‘woke.’

…which is what exactly?

References

ACLED. (2020). Demonstrations and political violence in America: New data for summer 2020. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

Brennan Center for Justice. (2022). Voting laws roundup: December 2022.

Equal Justice Initiative. (2017). Lynching in America: Confronting the legacy of racial terror.

History.com Editors. (2021). How Jim Crow-era laws suppressed the African American vote for generations.

National Archives. (2022). Executive Order 9066: Japanese American incarceration.

NAACP. (n.d.). History of lynching in America.

PEN America. (2024). Banned in the USA: Beyond the shelves.

The National WWII Museum. (n.d.). Japanese American incarceration.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025). Tulsa race massacre of 1921. In Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Tulsa-race-massacre-of-1921