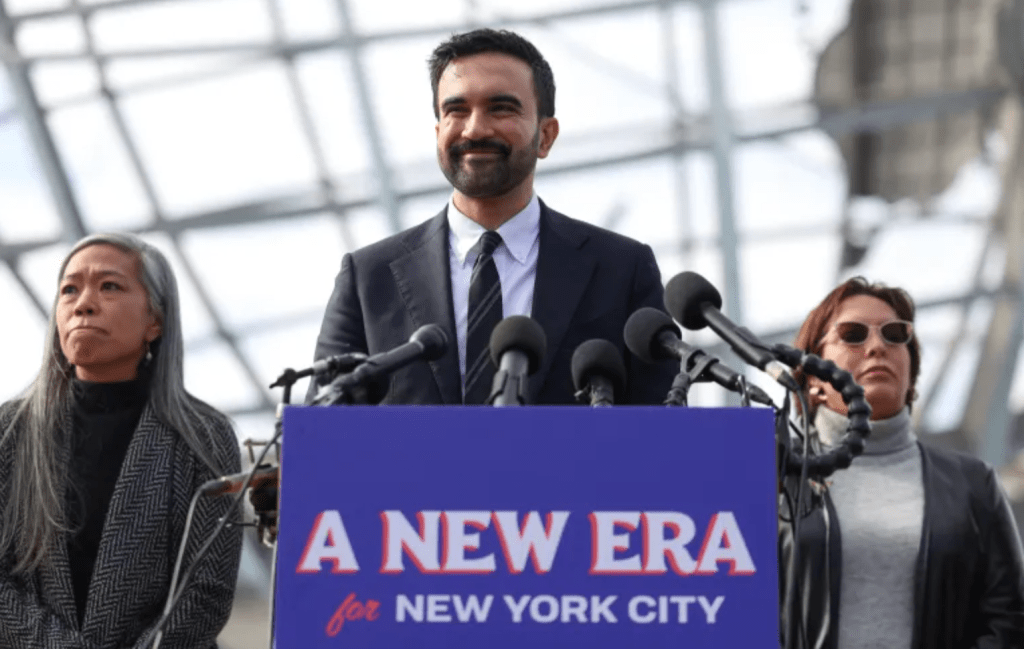

In the wake of Zohran Mamdani’s historic New York City mayoral victory, America was again reminded of its uneasy relationship with identity, power, and belonging. Mamdani, a Muslim of Ugandan-Indian heritage and democratic socialist, won on a platform rooted in affordability, public housing, and equity. Yet, much of the backlash he faced had little to do with policy and everything to do with who he was. Critics painted him as “radical,” “foreign,” and even the personification of 9/11, proof that even in a city built by immigrants, bias still has a powerful grip on the imagination.

But, what if these weaponized labels aren’t just political or cultural? What if racial prejudice operates like a mental illness—a disorder that aggressively distorts empathy, reason, and and one’s sense of reality into hostility?

Racism and Prejudice Are Not the Same

People often use the words racism and prejudice as if they mean the same thing, but they do not. Prejudice is personal—it is bias born from ignorance, fear, or assumption. Anyone can hold it. Racism, however, is prejudice backed by power, the ability to shape systems, policies, and opportunities in ways that privilege one group while disadvantaging another.

Prejudice shapes behavior, but racism shapes outcomes. Black Americans, for example, can hold prejudice, but not institutional power over housing, education, or justice. Racism demands both belief and authority—a structure built through slavery, segregation, and centuries of policy-driven inequity.

From redlining and Jim Crow to modern gaps in wealth, health, and incarceration, these systems turned the aftershocks of slavery into inherited barriers. The result is not past injustice, but a living architecture of disadvantage that still defines opportunity today.

This imbalance sustains delusion: the idea that control ensures safety, and sharing power means loss. That belief runs so deep it drives people to act against their own interests, defending policies that erode their healthcare, wages, and schools, so long as others lose more.

The Mamdani Example

Mamdani’s platform was not revolutionary. His ideas (e.g., rent freezes, fare-free buses, universal childcare, and higher taxes for corporations and millionaires) mirror the very foundations of modern American life: Social Security, Medicare, public education, and workers’ rights, etc. These programs, once believed to be “socialist,” are now pillars of stability. Nonetheless, when championed by someone with brown skin, a Muslim name, and a commitment to equity, they are suddenly viewed as extreme.

This contradiction reveals how certain words (i.e., “socialist,” “communist,” “radical”) function less as descriptors and more as dog whistles. They’re designed to invoke fear and herd specific segments of society towards defense of the status quo. Historically, these terms have been used to police who gets to lead, who gets to belong, who gets to define the American ideal and who gets to attain it. It’s not the policy that frightens people, but the perceived threat of a restructured hierarchy.

The Greatest Con Ever Sold

We see it every election cycle. Voters in struggling rural towns choose leaders who strip away their own healthcare, underfund their schools, and protect the wealthy few who exploit them. White farmers who once relied on government assistance now watch their subsidies vanish under the very administrations they supported. People vote for punishment, mistaking it for protection.

This pattern is not new. Whiteness itself was constructed as a political tool, an invention designed to give poor white men a sense of superiority over Black people. It was a strategy by wealthy elites to mask class divides, to convince struggling white workers that they shared status with their oppressors simply because of their shared skin color. It turned solidarity into suspicion and replaced common struggle with competition.

The result was control. Poor whites were pacified by proximity to privilege, while being used to police those deemed beneath them. The powerful profited twice: first by exploiting labor, and again by ensuring that those most exploited would never unite.

The Pathology of Power

Power sustained by fear and insecurity behaves less like strength and more like an unhealed trauma:

- Projection: Attributing historical cruelty to imagined retaliation.

- Paranoia: Believing equality means extinction.

- Avoidance: Denying responsibility by masking fear as patriotism or policy.

These are not the hallmarks of a healthy collective mind. They are symptoms of a deeper disorder, one that warps perception, dulls empathy, and transforms insecurity into aggression.

Healing the Disorder

Seeing racism as a mental disorder doesn’t excuse it. It demonstrates that progress begins with recognition and continues through accountability:

- Therapeutic intervention: Bias training, empathy-building, and exposure to diverse experiences can rewire reflexive fear.

- Community dialogue: Creating space for accountability, truth-telling, and reconciliation reduces isolation and projection.

- Systemic support: Addressing scarcity and inequality can calm the perceived threats that sustain prejudice.

Healing begins with acknowledgment, naming the illness, and refusing to mistake it for tradition.

Toward Recovery

Mamdani’s victory shows us that leadership rooted in inclusion can prevail. Still, the hostility he faces, rooted in paranoia and the illusion of “threat” (perhaps to certain individuals’ bottom line), reminds us how much work remains. Because bigotry does not simply fade with time; it feeds on fear.

It’s no different from clutching a red hot metal bar and swinging it to harm someone else. The heat radiates outward, but it sears the hand that grips it first, often far worse than any blow that lands. What was meant as a display of strength becomes one’s own burn to the third degree.

And if you believe that being progressive, a word that literally means moving forward, is somehow equivalent to the violence of racism—the chains, the lynch mobs, the centuries of sanctioned harm—ask yourself what it is you are truly afraid of.

That fear is misplaced, and the way it clouds judgment and distorts truth is exactly why racism should be seen as a kind of mental illness, one that feeds on imagined loss and blinds people to their shared humanity. And like any illness, it cannot be treated until it is first named and acknowledged precisely for what it is.

References

Allen, T. W. (1994). The invention of the white race: Volume 1—Racial oppression and social control. Verso. https://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1675310/e90f1c5c81cec6881594b6565110812e.pdf?1517359235

Banaji, M. R. (2021). Systemic racism: Individuals and interactions, institutions and structures. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00349-3

Carr, P. R. (2016). Whiteness and white privilege: A critical review of educational research and policy. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 7(2), 1-15. http://janeway.uncpress.org/ijcp/article/id/740/download/pdf/

CBS News. (2025, November 5). Zohran Mamdani claims victory in NYC mayor’s race, promises “relentless improvement.” https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/live-updates/nyc-election-results-2025/

Guardian. (2025, April 15). ‘Shock to the system’: farmers hit by Trump’s tariffs and cuts say they need another bailout. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/apr/15/farmers-trump-tariffs-bailout-extreme-weather

Lund, M. (2024). Whiteness. MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262544191/whiteness/

PBS NewsHour. (2025, November 4). Democrat Zohran Mamdani wins New York City mayor’s race. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/democrat-zohran-mamdani-wins-new-york-city-mayors-race

People. (2025, November 5). Zohran Mamdani, 34, defeats Andrew Cuomo to become N.Y.C.’s first Muslim mayor in historic election. https://people.com/zohran-mamdani-defeats-andrew-cuomo-nyc-mayor-election-11837136

Schouler-Ocak, M. (2021). Racism and mental health and the role of the psychiatrist. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 1-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8278246/

Scott, C. P. (2024). Unveiling whiteness: An approach to expand equity and deepen the field’s racial analysis. Journal of Social Issues, 80(2), 428-447. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12598

Shim, R. S. (2021). Dismantling structural racism in psychiatry: A path to equity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(12), 1099-1103. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21060558

The Guardian. (2025, November 5). Zohran Mamdani elected mayor of New York on winning night for Democrats. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/nov/04/zohran-mamdani-mayor-new-york-city

One response to “Diagnosing Racism: What Zohran Mamdani’s Victory Reveals About America’s Collective Disorder”

Hey Valencia,

I took some time to read through this piece, and I have to say, the way you broke down the distinction between prejudice and racism was powerful. The clarity of your framing, especially around how racism functions structurally rather than personally, brought a level of precision most conversations on this topic never quite reach. Your connections to Mamdani’s victory and to how certain labels operate as coded signals rather than genuine critiques were sharp and honestly refreshing.

What stood out to me most was how you articulated the psychological dimension — the way power, fear, and perceived loss distort reality. That’s a layer people tend to avoid because it forces an honest look at the mechanisms that keep harmful systems intact. The way you tied that into history, policy, and identity… it was brilliant. It felt like reading someone who not only understands the data, but the human condition beneath it.

And the point you made about racism behaving like a disorder resonated deeply, not in a way that excuses anything, but in how it shows the depth of the delusion and the internal damage it causes before it even translates outward. That was a perspective I hadn’t seen articulated that clearly before.

This was a strong write-up — thoughtful, layered, and unafraid to name what a lot of people dance around. I appreciate the work you put into it.

You highlight the structural and psychological dimensions of racism in America. As a Black woman and an epidemiologist, I imagine you’ve observed not only how bias manifests in individual moments but also how it’s transmitted and maintained across generations. How do you think these generational patterns interact with the broader social systems — the policies, institutions, and cultural norms — to perpetuate racial inequities? I’m curious how your lived experience and analytical lens together help you map the mechanisms by which racism persists over time.

LikeLike