Throughout history, language has been used not only to describe, but to distort reality. It can make cruelty feel like order, exclusion sound like good policy, and violence appear like it’s necessary for progress. Labels turn people into abstractions, helping those in power stay distant from empathy and accountability when moral clarity threatens their status quo. Beneath it all lies a psychological need to silence the piercing static that arises when actions fall out of tune with morality.

When Language Rewrites the Conscience

Cognitive dissonance describes the mental discomfort that arises when people’s actions conflict with their values. For those in power, language becomes a tool to quiet that discomfort. Rather than question harmful behavior, they reframe it. “Collateral damage” replaces “civilian deaths.” “Thug” replaces “teenager.” “Illegals” replaces “undocumented people.” These shifts make exploitation sound rational and injustice seem inevitable.

Dehumanization Through Language

Referring to groups without acknowledging their personhood, saying “Blacks” instead of “Black people” or “Orientals” instead of “Asian people,” turns communities into categories. These choices strip away individuality and culture. They reduce people to labels that can be managed, ignored, or erased.

This process is not new. During American chattel slavery, enslaved Africans were recorded as property in ledgers, not as people. During the Holocaust, bureaucrats used euphemisms like “final solution” to sanitize mass murder. Across history, labels have functioned as armor, shielding those in power from the moral weight of their actions.

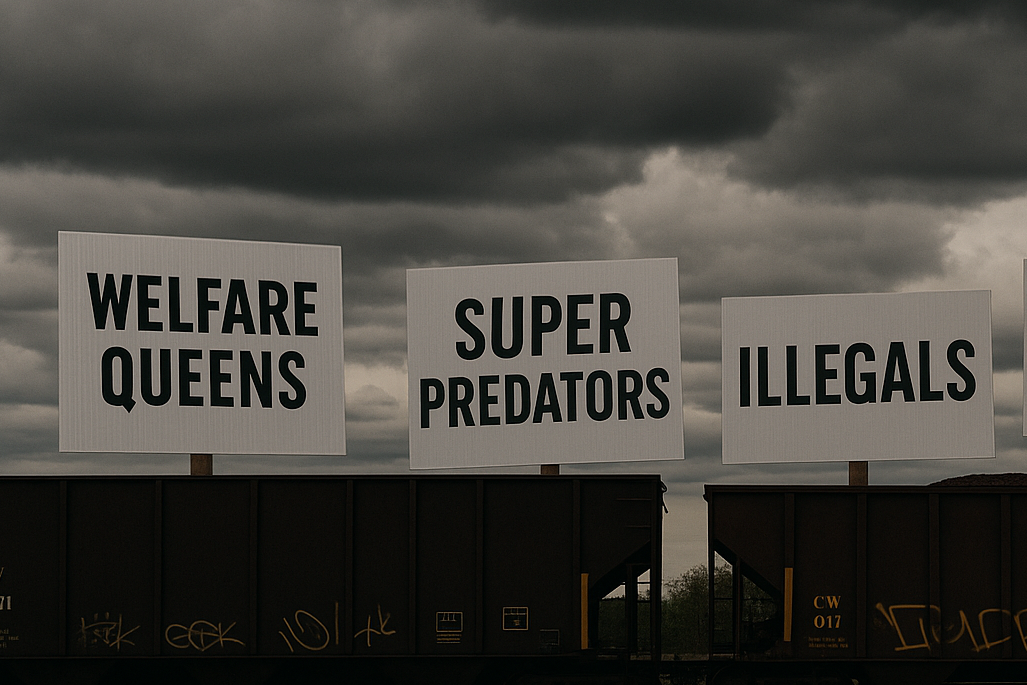

The American Pattern

In the United States, language has long served as a weapon of moral distancing. Colonizers called Native Americans “savages” to justify genocide. During Jim Crow, terms like “Negro” and “colored” reinforced hierarchies of worth. Today, the echoes persist: “welfare queens,” “super predators,” “illegals,” and “terrorists,” “antifa” instead of spelling it out, “anti-facists” are rhetorical cages that strip away humanity and invite suspicion to justify persecution.

When a group is labeled, their suffering becomes explainable, their mistreatment defensible, and their humanity negotiable. Once empathy fades, oppression can move forward unchecked.

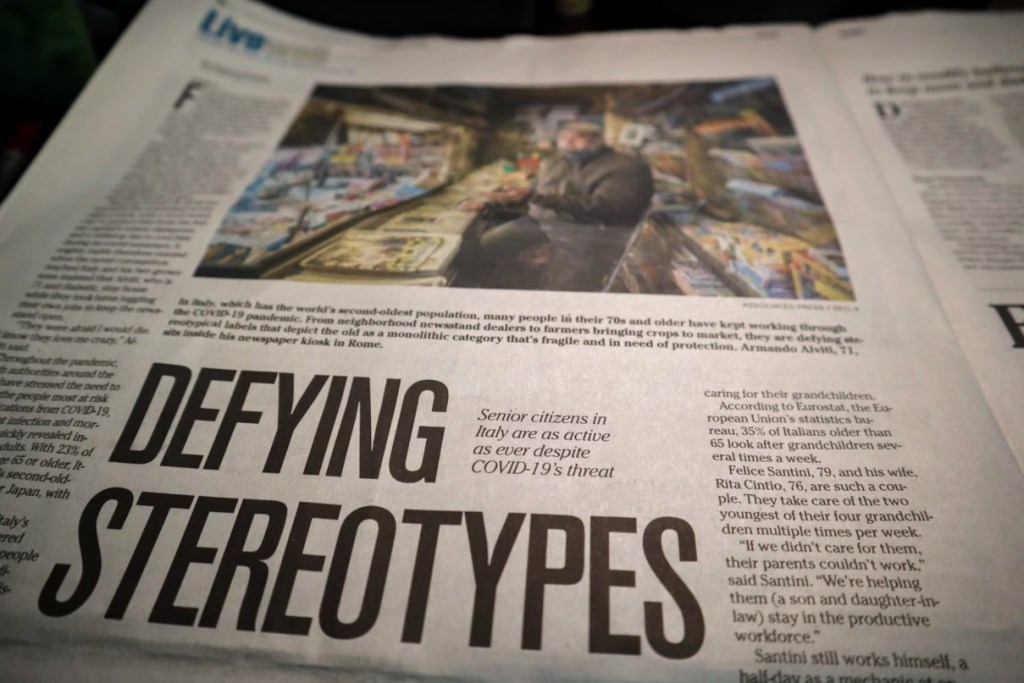

Modern Media and Everyday Speech

Ever notice how news outlets say “officer-involved shooting” instead of “police shot someone”? How protests led by people of color are labeled “riots,” while white protesters are called “demonstrators”? Or how bureaucracies refer to “detainees” rather than “people in detention”?

These choices aren’t neutral and they’re never harmless. They shape how the public assigns blame and empathy. And the people who craft them know exactly what they’re doing.

I explore this same idea in another piece, where I revisit ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’—this time through the lens of the bears.

What We Can Do

The goal here is not to be annoyingly politically correct, but to be intentional. To speak in ways that honor people’s humanity instead of reducing them to objectified categories. Ask yourself: Does this word acknowledge a person, or obscure them?

Be mindful of who benefits from the language being used. When you hear terms that dehumanize, challenge them. Replace objectifying language with person-first words that restore humanity and dignity. These shifts are not about politeness. They are about truth and decency.

Push institutions, media, and educators to use more accurate, human-centered language. Support efforts that make inclusive communication the norm rather than the exception. And most importantly, listen.

Marginalized communities have long explained how language has been used against them. Honoring how they choose to define themselves is one of the simplest and strongest acts of solidarity and respect.

Final Thoughts

Language is not neutral. It can build bridges or walls, affirm dignity or erase it. Again, the goal here is not perfection, but awareness. Every word either narrows the distance between people or widens the gap. Those who control language often control perception, but those who speak with intention can reclaim it and that is the power of the people.

References

American Psychological Association. (2021). Inclusive language guidelines. APA Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209.

Columbia Journalism Review. (2020). Stop using “officer involved shooting.”

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264.

Harmon-Jones, E. (2019). Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology. American Psychological Association.

National Institutes of Health. (2025). Person-first and destigmatizing language. NIH Style Guide.

The Associated Press. (2013). The Stylebook no longer sanctions the term “illegal immigrant” or the use of “illegal” to describe a person. AP Definitive Source.

The Associated Press Stylebook. (2021). Guidance: Avoid the vague jargon “officer involved” for shootings and other cases involving police.

Fernández Sánchez, H., et al. (2024). Language matters: Exploring preferred terms for diverse populations. Advances in Health Sciences Research.