For generations, many Black Americans have been raised with a message that was never meant to inspire per se, but primarily to protect: “you have to be ten times better than your counterparts just to be treated as equal.”

It was strategy and a rational response to a society that routinely changed the rules the moment progress for Black Americans and other marginalized groups appeared possible.

What’s often overlooked is how profoundly this mindset shaped not only survival, but skill. Over time, being forced to outperform did not merely foster resilience, it cultivated a level of proficiency that continues to influence American culture, labor, and innovation in ways that are now impossible to ignore.

Where the “10x Better” Rule Comes From

The expectation to overperform is inseparable from the history of racialized oppression in the United States. After the abolition of slavery, new systems quickly emerged to preserve hierarchy: Black Codes, Jim Crow laws, voter suppression, redlining, employment discrimination, and inequitable access to education and capital.

At each stage, advancement was met with resistance. As Black Americans pursued education, schools were segregated and underfunded. As they sought homeownership, redlining locked wealth out of entire neighborhoods. As they entered professional spaces, standards shifted: credentials were questioned, competence doubted, and mistakes magnified to the nth degree.

In response, families adapted. Children were taught to work harder, speak more carefully (& skillfully), arrive earlier, stay longer, and ultimately leave less room for error. Excellence became a form of protection. It wasn’t about perfectionism, but about minimizing risk in a system designed to penalize failure unequitably.

What Oppression Accidentally Teaches

When people are required to do more with less, they develop particular strengths. Constraint sharpens perception. Scarcity demands creativity. Constant evaluation trains anticipation.

Under slavery, even survival required innovation. Enslaved Black Americans were given discarded food scraps and turned them into sustaining meals like chitterlings and hog maws, transforming deprivation into nourishment and culture.

That same necessity-driven ingenuity extended far beyond food. Excluded from education, capital, and patent protections, Black Americans still engineered solutions to everyday problems. Garrett Morgan invented the modern traffic signal after witnessing dangerous intersections. Marie Van Brittan Brown developed the first home security system in response to delayed police response times. Gladys West’s mathematical modeling laid the groundwork for GPS systems used worldwide today.

These innovations were not born of excess or leisure, but created due to systems that failed to protect or serve Black communities, initially.

Over time, this environment produced skills now recognized as high performance: adaptability, strategic thinking, emotional regulation under pressure, and the ability to build without institutional support.

The irony is clear: oppression aimed at marginalized groups often sharpened the very capacities it sought to deny. In environments where help and grace were not guaranteed, survival depended on self-reliance and skill-building became unavoidable.

The Complacency Built Into Advantage

By contrast, those who benefit from systems designed to work in their favor are rarely required to cultivate the same level of agility. In the United States, access is often inherited rather than earned—through legacy admissions, generational wealth, nepotism, and social networks that quietly convert proximity to power into opportunity. This does not mean life is universally easy for White Americans; struggle exists across all groups. But the baseline is different. Structural, systemic, and societal biases consistently disadvantage Black Americans and other marginalized groups while insulating many White Americans from the most severe consequences of failure.

That difference in baseline shapes behavior. When access is assumed, failure carries fewer lasting consequences. When the rules are stable and written with you in mind, adaptation becomes optional. You are less often required to anticipate sudden shifts, repeatedly prove competence, or build safeguards simply to survive.

This is not a moral judgment, but a structural reality. Comfort dulls urgency. Advantage can reduce curiosity. Over time, systems that buffer risk can also slow growth, producing stagnation in some, even as others continue sharpening skills out of necessity.

That contrast is no longer subtle. It has grown increasingly visible.

The Pendulum Isn’t Swinging Back—It’s Moving Forward

There’s no denying that this moment is hard. For many, it has meant discriminatory or targeted layoffs, shrinking access to institutions that once promised opportunity, and a renewed sense that the rules are being brazenly rewritten…again like clockwork. That reality is destabilizing. It’s exhausting. And it should not be minimized.

Nonetheless, difficulty does not negate direction.

What we are witnessing now is not the collapse of standards, but the exposure of who was never trained to meet them without privileged advantage. Just as importantly, it’s a signal (and reminder) that reliance on those systems was never meant to be permanent. The backlash so often labeled “anti-woke” is not strength asserting itself, but insecurity reacting to a perceived loss of control.

Those raised under the “10× better” rule are not unfamiliar with this terrain. They have navigated shifting goalposts before. They know how to adapt when access is restricted; how to thrive under pressure; and how to build when permission is prohibited.

This moment is not an invitation to retreat. It is a reminder that we need to have, should have, and must continue to build our own (i.e., our own institutions, pipelines, capital, networks, and definitions of success)—not out of spite, but self-determination and self-actualization.

Fear of the Future and a Misreading of It

Much of the resistance to equity we’re witnessing in America is rooted in fear: the belief that as power shifts, those who were once dominant will be treated the way they historically treated others. This assumption reveals projection more than reality.

Black Americans, in particular, understand a truth often missed in these anxieties: lions do not concern themselves with ants. The pursuit has never been dominion or superiority. It has been survival, dignity, and wholeness. Despite centuries of deliberate attempts to sever Black people from their history, culture, and power (from enslavement to erasure) there remains a deep-rooted security in identity that does not require subjugating others to affirm itself.

Historically, marginalized groups have not advocated for reversal, but for repair. The dominant vision articulated by Black scholars, activists, and communities has emphasized shared progress rather than domination and expansion rather than replacement.

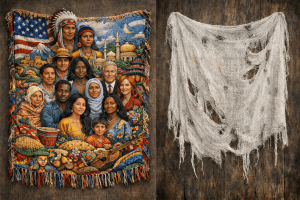

The metaphor that best captures this vision is not displacement, but tapestry: a society strengthened by difference, where resilience comes from variation and overlap, not uniformity.

The Quiet Outcome of Being Forced to Be Better

The future does not belong to those who cling to static power. It belongs to those who learned early that survival requires movement, evolution, and collective ingenuity.

Oppression was designed to limit possibility. Instead, it cultivated excellence.

That irony does not erase the harm. It does not justify the cost. But, it does explain why those trained under pressure are often best equipped to navigate uncertainty while those who relied on unexamined advantage struggle when the ground shifts beneath them.

And that is a reality no amount of backlash can undo.

References

Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New Press.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2018). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (5th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Coates, T.-N. (2014). The case for reparations. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing.

Wilkerson, I. (2020). Caste: The origins of our discontents. Random House.